He longed for cleanliness and tidiness: it was hard to find peace in the middle of disorder.

— Robin Hobb, City of Dragons

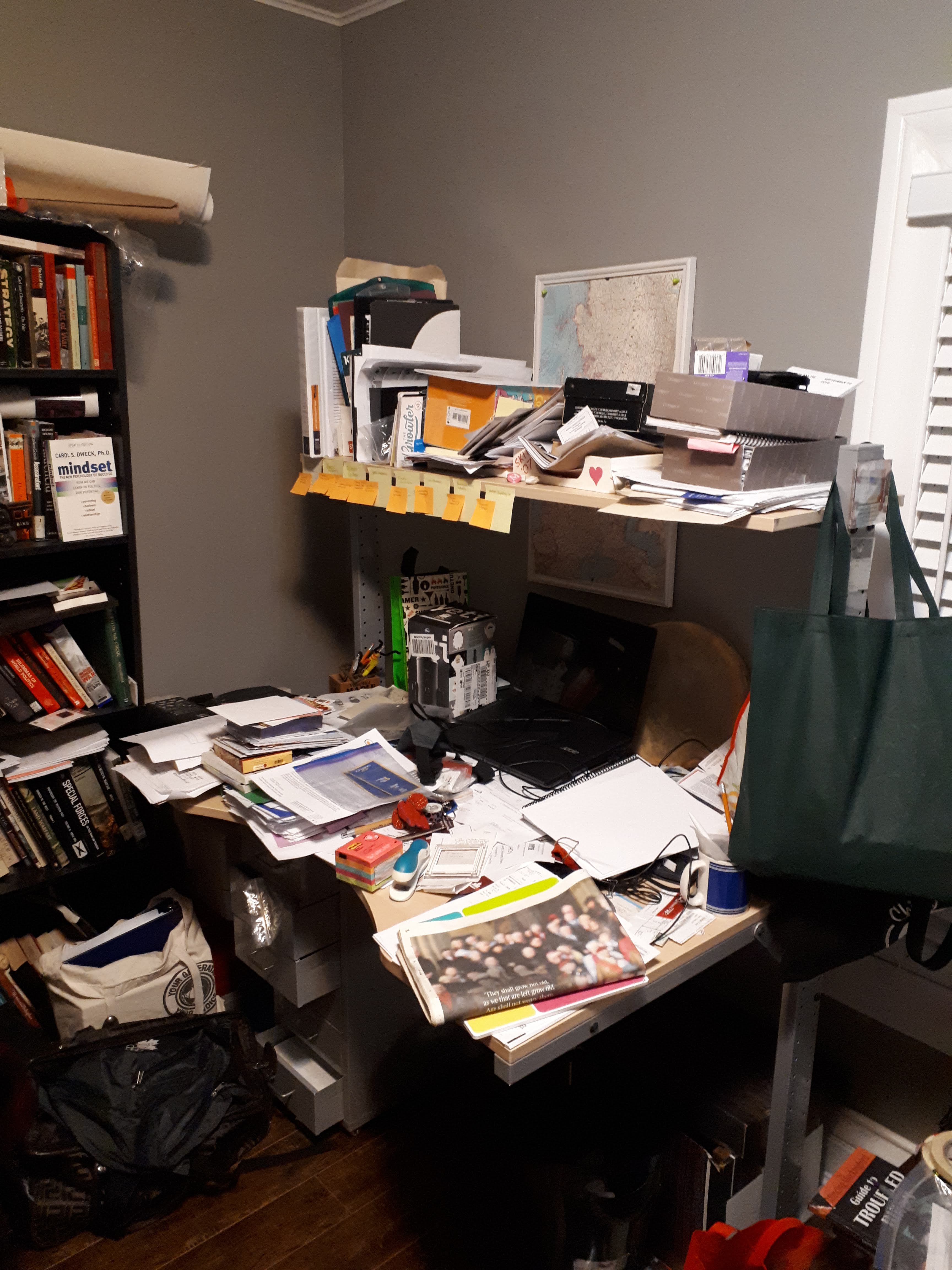

There is a lot written about clutter: what it says about your personality, your mental health, your relationships, your productivity. Invariably, any article, blog post, or piece of motivational home decor contains a variation on the phrase “a cluttered space is a cluttered mind” (or is it the other way around?). I’m not sure which comes first, but I can tell you that when I look at the desk in my home office, part of my brain starts to scream. So much so, that I have become quite adept at pretending it doesn’t exist. Until, of course, I need to find that all-important tiny slip of paper buried in one of the piles. So this week I committed to organising my desk at home. Sounds easy enough, right?

While I have no doubt that the psychological study of clutter is indeed fascinating (“hoarding disorder” occupies its own place in the DSM-5) the cultural fascination with people and their belongings is much less scientific. There are entire reality shows built on the premise of labelling an unsuspecting person as a hoarder, bringing a stranger with dubious credentials (and network cameras) into their home, and literally airing their dirty laundry to the world, all to “help” them. I almost wish they would film a 10 year follow up to see if the subjects’ lives have really changed and if they are still in contact with the family and “friends” who nominated them.

The collection of “things” is an enormous field of study occupying a place in psychology, sociology, anthropology, and social, political, and economic studies. You cannot hope to have a meaningful conversation about possession, consumption, and stuff without considering the impact of privilege. Enter the cultural phenomenon of “minimalism”.

Before I get into the weeds here (and I promise I will get back to my own desk), I should issue this caveat now: my two undergraduate-level psychology courses do not make me an authority on the brain chemistry involved in our relationship with “stuff”, so my observations are entirely my own and are not backed up in any meaningful way by science.

Minimalism

I don’t know when I first became aware of this word outside the context of the post-WWII visual arts movement, but one day I turned on my computer and the world was full of books, websites, lifestyle blogs, Pinterest pages, and documentaries all dedicated to changing your life by getting rid of your possessions and becoming a “minimalist”. My first foray into minimalism was through a documentary about two guys: Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus. I tuned in out of curiosity and I learned that as they were about to turn thirty (sounds familiar) Joshua and Ryan “had achieved everything that was supposed to make [them] happy: six-figure careers, luxury cars, [and] oversized houses…” (okay, not quite so familiar). It was a tale as old as time: they realised that despite all of the stuff, they still weren’t satisfied. They gained stress, debt, guilt, and depression, and they lost control of their time and their lives. So in 2009, they gave it all up and embraced the principles of “minimalism”.

I have to admit, it was fascinating watching two people voluntarily give up the “American Dream” because the lifestyle we are all programmed to desire was no longer making them happy. It was also somewhat soothing to ignore the actual context of their lives and watch them operate in a world with fewer physical objects tying them down. They had time, freedom, money, and a life that could be packed into a single suitcase. Nothing was stopping them from living a mobile, care-free, bohemian lifestyle.

Here’s where the context returns and the privilege comes in. The way we interact with the physical objects in our world is an intense signifier of class and privilege. I would argue that minimalism, the way it is currently portrayed, is the new “conspicuous consumption”: simply another way for people to carefully curate possessions to signal class. The “hoarders” I mentioned before? Usually people living regular lower- to middle-middle class lives who make a decent wage and support their families. I challenge anyone to find an episode that takes place inside a palatial mansion or a chic New York City apartment. To make a radical life change, to quit your job to pursue a passion project, to get rid of your car and design the perfect capsule wardrobe is only realistic if you have the income and means to support yourself and your dependants. True, not impulsively buying things is an easy way to keep money in your bank account, but redesigning a life takes time and money. Privilege.

This isn’t to say that Millburn and Nicodemus aren’t onto something worthwhile. While I felt alienated by the circumstances that allowed them to pursue their new lives (hold on while I sell my Lamborghini to finance my tiny-house), I was inspired and motivated by the mental load being lifted. I may poke fun at their expense, but when I look at certain rooms in my house, certain closets full of boxes, my desk, my brain goes haywire. Some of the things I currently own do stress me out. Looking at the physical clutter creates mental clutter. But on the other hand, some of the objects in my life make me smile, remind me of someone special, make me proud, and even spark joy.

Tidying Up

I really got into minimalism shortly after we moved into our first apartment. It was the first space we had lived in together and there were some growing pains as far as “stuff” was concerned. I laugh now thinking about the ordeal of moving. I was born and raised in London (lots of stuff there) but I lived in Peterborough (stuff there too), while my Mum and her possessions were from Shelburne (furniture, heirlooms, keepsakes) and my husband was from Fort Erie (every object he encountered in his life). So we moved belongings from four houses in four different cities into a two-bedroom apartment in St. Catharines.

I lived on my own from the time I was 17, so everywhere I went I had enough around me to allow me to function: clothing, furniture, kitchen appliances, toiletries, day-to-day things. When we moved into our apartment we had those things plus every book, participation ribbon, old report card, and memento from our time on the planet that our parents were only too thrilled to get out of their house. All the stuff that we completely forgot about. We had to very quickly figure out what fit into our lives, what made sense to keep, and what we could get away with holding onto “until we may need it”. It was at this time that I thought a quick peek into minimalism wouldn’t go amiss.

On an internet list of all places, I saw a recommendation for a book titled The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo. I will say right now that Marie Kondo and her method of “KonMari” is not minimalism. In fact, the first thing you read on her website is the following text:

“KonMari Is Not Minimalism

KonMari Philosophy, Notes from Marie (konmari.com)

Focusing on what to discard obscures the most important part of the KonMari Method™: choosing what to keep. Minimalism champions living with less, but Marie’s tidying method encourages living with items you truly cherish.”

Already this approach was sounding a little more user-friendly. The goal is not to eliminate any trace of material possession, but to organise your physical space in order to cultivate joy. Owning and being attached to your possessions is not shameful and there is no inherent moral superiority in the minimalist aesthetic. Your relationship with the things around you is personal and any change you make should be meaningful and taken without regret or remorse.

Marie Kondo has a set of guidelines that are a fine place to begin; however, it is not imperative that you obey every one to the letter. She recommends no more than a small number of books, and when I shared this with my husband we both looked at each other and laughed. Owning many books makes us happy. We feel a sense of pride and awe at the collected knowledge around us. The aesthetic of a full book shelf is both calming and energising. Every single one of them brings us joy.

Tidy Your Desk

Did I tidy my desk or did I get bogged down in the philosophy of materialism? I think the latter is probably a safer bet, but I think I can tie everything together nicely, if you’ll bear with me for one more minute.

Yes I did tidy my desk, with the operative word being “tidy”. My desk is not “minimal” nor does everything on it “spark joy” (believe me, my file of utility bills leaves a lot to be desired). The most important thing I took away all those years ago is that regardless of what Religion of Stuff you subscribe to, life always wins. I would have jumped into the KonMari Method™ with both feet if I lived alone and had complete control over what entered and exited my home. Instead, I live happily in a house with my husband and his physical contribution to my life is a privilege. We couldn’t live a purely minimalist life, even if we wanted to (which by its strictest definition, we don’t). Over the years we have collected art that we cherish. The furniture I inherited is beautiful and it reminds me of my Mum whenever I look at it. We have about a thousand objects in our kitchen because we love to cook and our kitchen is the heart of our home.

Yes, life wins. But I think we can work with life intentionally to make the most out of our space and our possessions. While I was working on this week’s task, I was also planning a surprise party for my husband’s birthday, hosting two people in our spare rooms, and working full time. I wasn’t able to spend as much time going over my desk as I would have liked, but I became okay with life taking over this week. I will finish my desk and I will continue to collect, discard, and interact with objects more intentionally because meaningless clutter creates mental chaos, but a tidy(-ish) existence full of people and things that I love makes me happy.

Sources

45 Things You Can Do to Get Happy No Matter Where You Are

Courtney Johnston | @CourtRJ | ( http://www.rulebreakersclub.com/) on Lifehack.org

48 Little Things You Can Do to Make Yourself Happier Now

Elyse Gorman | @notesonbliss | ( https://elysesantilli.com/ ) on Thought Catalog

Managing a Hoarding Disorder Batya Swift Yasgur, MA, LSW | Psychiatry Advisor

Minimalism: Another Boring Product Wealthy People Can Buy Chelsea Fagan | @chelsea_fagan | The Guardian

The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organising by Marie Kondo

The Minimalists | Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus